So, how are those inflation-indexed Treasury securities working out for you?

Oooh. Sorry. Sensitive question?

Neil Irwin paints the big picture (emphasis added):

Two separate events from the last few days, on two different continents: In the United States, a messy series of negotiations over how to avert the fiscal cliff and bring down the nation’s large budget deficits seemed to be heading nowhere. In Japan, a land of the largest public debt in the world relative to the size of its economy, a new government was elected pledging to pressure the nation’s central bank to inflate the money supply much more.

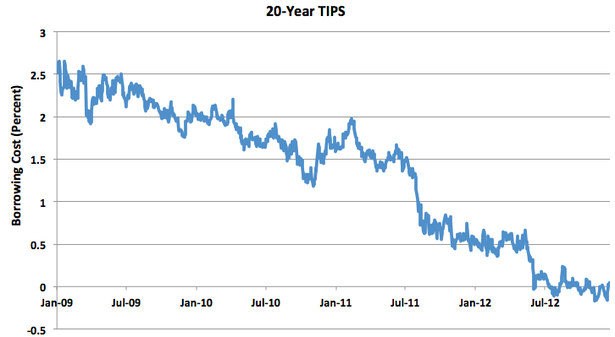

Here are two numbers to know about the United States and Japan: 1.79 percent and 0.77 percent. Those are the yields on 10-year bonds in those two nations as of Thursday morning [Dec. 20, 2012], the price their governments must pay to borrow money for a decade. In other words, investors are willing to fling their savings at those two seemingly dysfunctional governments for next to nothing.

But it’s not just the United States and Japan. Name a country with three elements—a stable political system, a credible central bank to call its own, and a free flow of capital across its borders—and it has, right now, extraordinarily low interest rates. That’s true for Canada and Australia (10 year yields of 1.85 percent and 3.36 percent), of Switzerland and Sweden (0.55 percent and 1.6 percent). Britain, certainly (1.94 percent), but even some countries that don’t technically fit our classification because they lack their own central bank (Germany at 1.42 percent and France at 1.99 percent. That would be the same France that The Economist, in a cover story last month, called “the ticking time bomb at the heart of Europe.”).

So what is going on? Interest rates are, essentially, the relative price of money today versus its value in the future. And investors are saying that they don’t need very much compensation to delay their spending for the future, as long as they can feel secure that they will get their money back and that the money they get back will be worth roughly what they put in.

To put it a different way, around the world there are all sorts of savers—pension funds, wealthy individuals in emerging nations, governments that want to ensure they have reserves put aside in case there were to be a run on their currency—for whom the goal is not so much to get a big yield on their savings, but rather to ensure that they will get their money back when they need it.